There are at least 45,000 undocumented children across Iraq following the fall of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL or ISIS). Even though Amira Hussein Ahmad holds an approved copy of the government issued documents for her second undocumented child, Hajar, she is struggling to obtain an ID because Ahmad's husband was with ISIS. Khazer IDP camp, April 2019 for Al Jazeera.

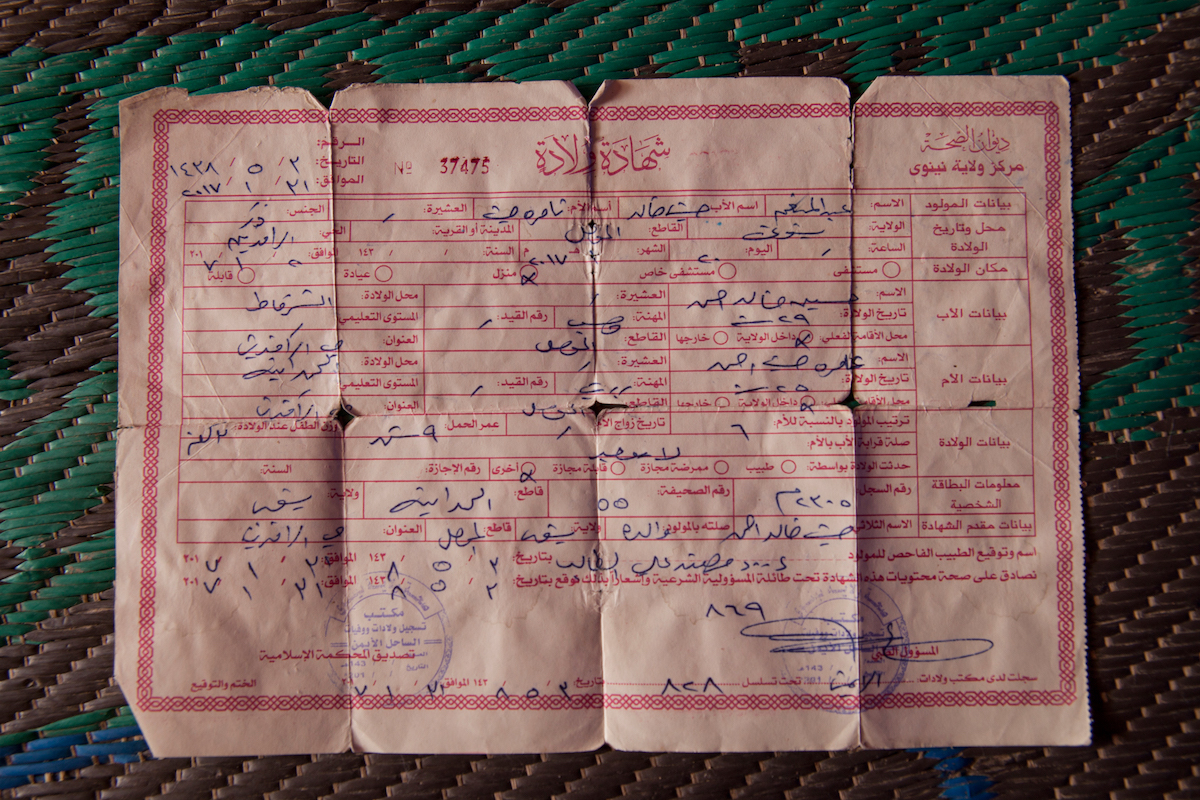

When ISIS was in control they issued their own documentation, such as this birth certificate for Abed al Menaaem, the youngest child of Amira Hussein Ahmad in Khazer IDP camp. Children in this situation, now without Iraqi IDs cannot access education and healthcare.

Children are undocumented due to having lost their Iraqi government-issued identification when fleeing ISIS, having them confiscated by the terror group, or only have birth certificates issued by ISIS – which the Iraqi government won't recognise – because they were born in areas controlled by the group.

As ISIS were being driven out of the territory they held, they purposely laid IEDs behind them making the areas uninhabitable possibly for decades to come. Unexploded ordnance are still being cleared in Mosul. Local clearance officer, Khudar Yasine, points out how hook line cables are attached to objects, which may conceal IEDs, enabling them to be removed without added danger. April 2019 for Al Monitor.

Al Shifa in West Mosul was once the second major hospital in Iraq. Over 3,000 IEDs have been found in the Al Shifa hospital complex alone in the last 16 months, including; grenades linked to detonators, mortars, metal pressure plates buried in the ground, and air dropped ammunition, all which if interacted with, can cause death.

Once IEDs are detected, they are rendered safe by hand – cutting the wire in this instance.

Mechanical searches are undertaken by excavators digging and distributing rubble, then to be searched by eyesight for IEDs.

Despite the significant damage perpetrated by ISIS, Al Shifa hospital complex has been assessed by structural engineers who state 86% of the buildings are salvageable in one way or another.

Not only has conflict, in recent years, moved from the rural to the urban environment, the weapons used have become more dangerous. Traditional mines only had 242g of high explosives, now IEDs contain 10-20kgs, subsequently increasing fatalities.

Coalition air strikes designed to corner ISIS in the western part of Mosul partially damaged all five of the city's bridges. ISIS then completely destroyed two of then in an ultimately futile effort to stop the Iraqi army from advancing on its stronghold. The Fifth Bridge (pictured) is one of two temporarily reconstructed bridges in Mosul in the last two years. Residents are frustrated by the slow efforts to rebuild due to government corruption. July 2019 for Al Jazeera.

Al Nuri Mosque by night. Built in the 12th Century it was the heart of Mosul. ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi declared their so-called caliphate at the mosque in 2014, and it was destroyed in fighting between government forces in 2017.

The Old City of Mosul two years on from liberation from ISIS. The majority of the city was destroyed by coalition aerial strikes as ISIS fighters hid in the narrow alleyways and took over houses.

The Old City of Mosul two years on from liberation from ISIS. The majority of the city was destroyed by coalition aerial strikes as ISIS fighters hid in the narrow alleyways and took over houses.

A man sells prayer beads in the Qaisary Bazaar, Erbil, Iraqi Kurdistan.

Men take a break from transporting goods in the Qaisary Bazaar, Erbil, Iraqi Kurdistan.

Handmade flutes in the Qaisary Bazaar, Erbil, Iraqi Kurdistan.

In Iraq's southern region of Basra, climate change and the cutting of important river flows is threatening the environment, farming and livelihoods. The following related photos are for New Lines Magazine and Thomson Reuters Foundation. 2022.

Buffalo are sent out each morning to go and swim in the ever decreasing waters of the Iraqi Marshlands, in which the ecosystem and human life dependent on it is described as endangered by the UNDP.

For those who live in the marshlands which spand across Iraq and Iran - the "Marsh Arabs" - they depend on buffalo and their milk to survive. They depends on the marshes.

Fatima's buffalo no longer produce milk because she can no longer buy the bags of wheat for them to feed on, considering they come back from grazing still hungry as grass no longer grows due to lack of water and scorching heat.

Fatima stands next to her beloved buffalo, with a grave face she says how concerned she is about the marshes salty water because they can no longer drink from it.

Though Thama Hataha’s family have lived in the marshes since “Adam and Eve,” he says the situation has never been more dire, and they no longer make a profit from the buffaloes’ dairy products due to having to buy them feed.

Thama Hatahat’s wife Noor, says their children know only the marshes, and if they were forced to move to the city to find work they would lose their culture and she wouldn’t recognise them.

The water of the marshes is now “poisoned” due to the rivers flowing into them carrying industrial waste meaning the grass along the banks has died and Thama Hatahat has to buy wheat to keep the buffaloes alive.

Those who live in the marshes build their houses from reed, which need to be refreshed every year, but reeds are declining in growth due to the decline in water.

The buffalo are traditionally the main source of income for the people of the marshes, though food sources for them are drying up and the now salty water endangers them, forcing their owners to buy food and truck in fresh water.

Umm Ali is the sole provider for her family and is worried she will have to beg for food this summer as the marshes dry up more and there is less fish to catch and sell.

Fishing since he was six years old, Ahmad Attasalah can see a sharp difference in the marshes over the years, particularly in the last year there has been overcrowding of fisherman in concentrated areas due to the decreasing water.

Hussein Ibrahim walks through the only section of his 20 dunums of land which can now be planted, in Al Fao, Basra, due to excessive salinity in the soil.

Lands between Al Fao and Abu al Khaseeb in Basra are left barren as farmers have given up on growing crops in extremely saline soil, the result is desertification.

Extreme desertification and soil salinity between Al Fao and Abu al Khaseeb in basra province.

Basra region in Iraq has been labelled the 5th most vulnerable in the world to water scarcity and desertification by the UN, the cracks in the ground on Hussein Ibrahim’s farm shows the little rainfall in the winter does nothing to moisturise the earth.

The Shatt al Arab used to fill this small pond on Hussein Ibrahim’s land in Al Fao meaning he could also breed fish, but they all died due to the salinity in the water.

Three years ago, Hussein Ibrahim had 30 sidr trees, now he only has three, one of which appears to be dying from lack of rain this winter. The harvest of each tree would be $300.

Hussein Ibrahim has been growing Henna since 2003, but each year his crop depletes and the foliage drops off due to high salinity in the soil.

Federation of Farmers Association in Basra Abd Al Hussein Al Abadi, at his office in Basra, stressed that government support is essential in order for farmers to stay on their land as they continue to make losses it the face of climate change.

Iraqi Ministry of Agriculture al Qurna Research Department head Mujtaba Noori is planting hybrid wheat seeds and testing them for resistant to salinity and wind.

Haidar Sabah Radi, 40, made the tough decision to move his whole family to the village of al Qurna from his farm 8km away in order to make more money driving a taxi.

Sandstorms are becoming more frequent in Iraq and with this comes a reduced wheat harvest for Hadi Badr al Malaki in al Qurna.

Wheat farmer Hadi Badr al Malaki, 57, already has one son who has moved to work in the government sector to help support the family considering a fixed salary is “safer” than farming in these conditions.

The Shatt al Arab river running alongside Abu Mohamed’s farm no longer reaches a level to irrigate his fields from the water, which is also increasingly becoming salinized due to lack of rain.

“If all these palm trees are gone, I’ll be gone too, my life is about these palm trees,” says Abu Mohamed as he looks up to the withering tops of the date palms.

This winter’s tomato crop of 400sqm is destroyed by a new fungus, which Abu Mohamed believes is due to extreme weather.

Abu Mohamed has been farming all his life in the village of Abu al Khaseeb, but with the complete loss of his recent winter crops, he is thinking to plant cucumber and radish instead of okra and eggplant, to see if they are more resistant to new diseases.

Abu Mohamed will leave his dying okra plantation in the ground for the University of Basra to visit and conduct research on the new types of fungus growing this season.

Abu Mohamed points to the amount of dust accumulated on the greenhouse of his crops from the last sandstorm.

The palm trees on Abu Mohamed’s land in Abu al Khaseeb are now stunted due to the lack of rain and salinity in the soil.

Farming is part of Abu Mohamed’s soul, though with the constant crop losses due to a lack of water and environmental changes he is becoming desperate to look after his family and is thinking of moving north.